“At one point, we all consciously decided how much to eat and what to focus on when we got to the office, how often to have a drink or when to go for a jog. Then we stopped making a choice, and the behavior became automatic.”

So writes Charles Duhigg in his bestselling book, The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business. The passage is a powerful reminder that virtually every behavior, no matter how small or routine that behavior, began with a choice—a conscious decision. Aside from involuntary processes such as breathing or sleeping, there’s an intention behind everything we do.

The same is true for our organizations. Every workforce program, every internal system, every element of company culture would not exist if someone hadn’t thought, “let’s do it this way.”

How Habits Get Formed

Think of an everyday occurrence at your organization—something that just seems to happen, like a lunch break or vehicle inspection procedure. Can you remember the moment it stopped being a conscious decision and became an unconscious habit?

Don’t be surprised if you can’t. According to Duhigg, the conversion of decision into habit is “a natural consequence of our neurology.” The human brain is built to form habits, perhaps because habits allow us to, you know, live our lives. If you had to consciously think about everything you do before you did it, you probably wouldn’t be able to get very much done.

The problem is that once a habit is formed, it tends to stick—whether we want it to or not. While the brain is excellent at creating routines, it struggles to disrupt and dislodge them. And even though our conscious minds can tell the difference between a good habit and a bad habit, between a healthy and an unhealthy routine, our unconscious selves don’t seem to care.

How Safety Habits Can Be Changed

To the habit-forming brain, what we do is just what we do—because that’s the way we’ve always done it.

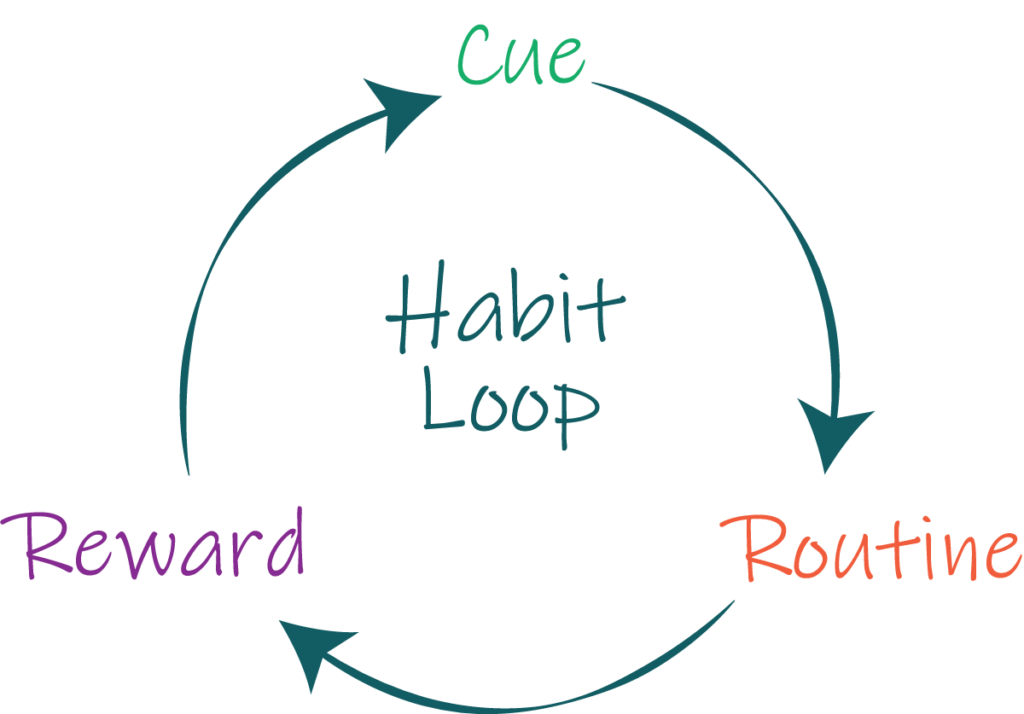

That doesn’t mean we’re powerless over our habits, however. Unconscious behaviors can be changed; new routines can be set. The key, according to Duhigg, lies in understanding “habit loops.” He writes that each behavior consists of a habit loop, comprised of three components—a cue, a routine, and a reward. One thing leads to the next and then, like a loop, it repeats.

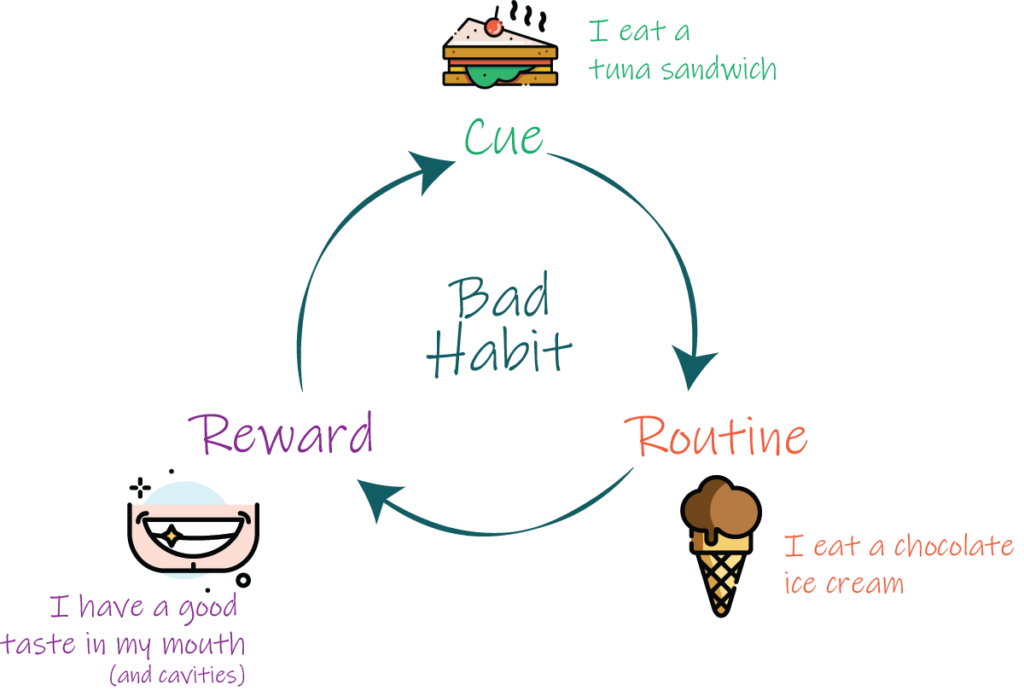

For example, let’s consider a bad habit: not brushing your teeth. Here’s what that loop might look like:

- You finish eating a tuna sandwich. That’s a cue—in this case, a cue you’re done with the main course, and you have tuna breath.

- You don’t brush your teeth, because you hate the taste of minty toothpaste mingled with tuna. This fixed belief both reflects and encourages a routine—the more you do something, the more ingrained the behavior becomes.

- You follow up dinner with chocolate ice cream. The yummy taste of chocolate is the reward—but that reward comes at a cost. Just ask my dentist!

Yes, bad habits have rewards—that’s why they’re so hard to break. As this example demonstrates, the brain can fall for a short-term reward even though when the overall habit causes damage over time. We all know what happens when we don’t brush our teeth.

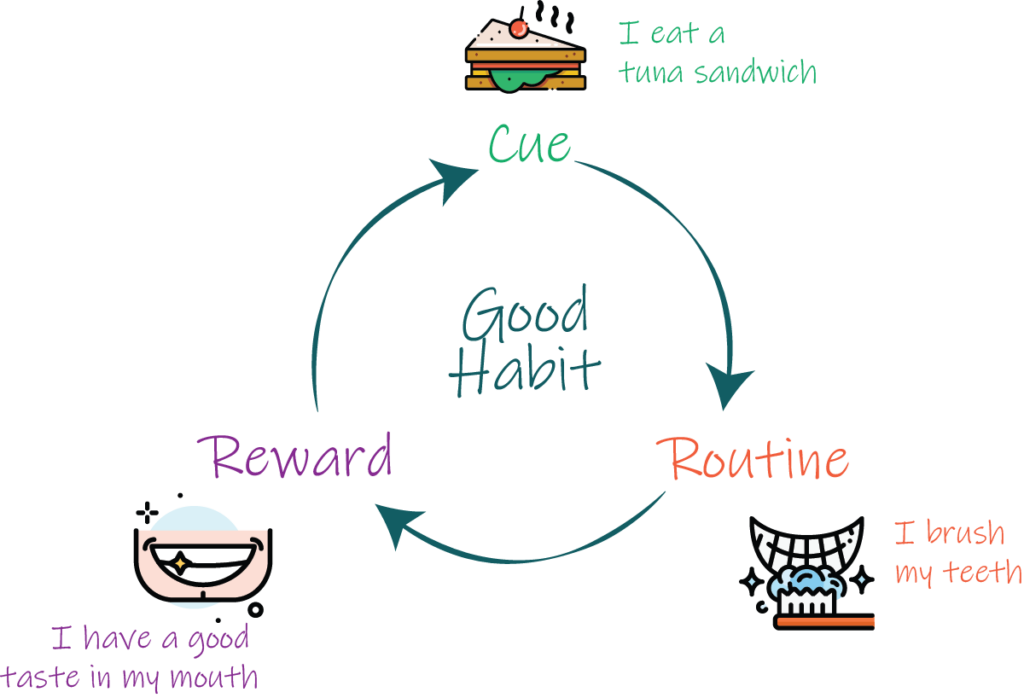

Fortunately for anyone who enjoys the complementary flavors of tuna and chocolate, an expensive visit to the dentist isn’t the only possible outcome here. Difficult though it may be, bad habits can be broken.

How? By fiddling around with the components of the habit loop. If you can change the cue or the reward, writes Duhigg, you can change the routine. Let’s reframe our example, starting with a different cue.

- You finish eating a tuna sandwich. Your teeth feel dirty, and tuna breath rears its’ ugly head—that’s your cue.

- You brush your teeth, initiating a new routine.

- As a reward, you enjoy the tingly effect of the toothpaste.

How to Bring Better Safety Habits into the Workplace

We’re not just talking about oral hygiene. The workplace is full of habit loops—some negative, some positive.

In The Power of Habit, Duhigg tells the story of renowned NFL football coach Tony Dungy, who used habit psychology to bring the Tampa Bay Buccaneers up from the bottom of the League.

Dungy’s theory was that players were overthinking and overanalyzing their moves. A defensive player had to look at the lineman, the running back, the quarterback—their legs, their hips, their movement—as well as determine whether there were gaps in the line, whether to run or pass, whether to throw the ball to the side or away. Dungy recognized every one of these elements as a potential cue in a habit loop. He saw that players had too many cues to choose from, and that their reaction times were delayed as a result.

Dungy coached his team on one cue at a time. First, he had them focus on the running back, then drilled and drilled the play. Then, he moved on to the QB and drilled that play. And so on—until each cue became a singular, rapid-fire step in the routine instead of the defense trying to look at everything at once.

The Buccaneers’ reward? They became division champions—and went on to win a Super Bowl.

To bring the same success to their organizations, workplace safety leaders need to think like Dungy. That means seeing a situation from a worker’s perspective, planning strategically around the various steps and decisions involved, and—perhaps most important—having the patience to train, train, and train some more. Keep in mind that Dungy didn’t try to change his team’s entire defensive playstyle all at once; he helped them develop and practice habits for every unique scenario they might face.

And Dungy’s journey with the Buccaneers is one example among many. Take a look at how 3 companies established positive habits to create effective, industry-leading workplace safety cultures.

And then, here’s your homework…

- List out the bad safety habits you can find in your workforce.

- If you dig in, you can identify the habit loops that are reinforcing them?

- Can you rewrite these loops by substituting bad for good?

- Extra credit: can you reinforce these new habit loops through by automating them? This is where EHS software like Vera EHS comes in real handy.